normal rockwellian

current view of farm I grew up on 1953-1960 – foto by Stone Ranger

Here is a portion of chapter 1 of Criminal by Smith & Lady.

This describes life on a 40 acre farm 9 miles south of Spokane Washington where I lived from the ages of 7 through 14 (1953-1960). It was a time of Norman Rockwellian innocence for me. Yet the first thing I did when we moved into the city was steal 13 cars.

~ ~ ~

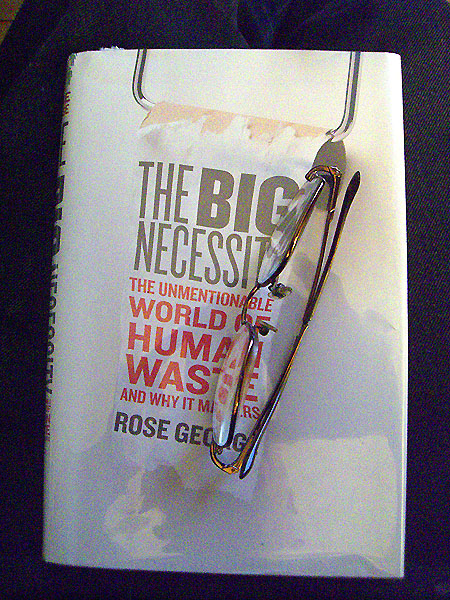

On a farm, you plant the garden, and it grows. You milk the cow at six o’clock in the morning and six o’clock at night. You feed the chickens once a day, the pigs once a day, the rabbits, ducks, geese. You feed the cows some grain while you’re milking, and they graze in the field the rest of the time. Once a week you shovel the chicken shit. There’s more work when there’s killing to be done, but it’s not all that bad, except for cleaning the pig pen. Pigs are bad because they seriously stink. And they’re smart. If they can find a way to screw you, they will. They’re hefty critters too, a lot larger than people realize. And fast.

I watched my father kill pigs and calves and lots of chickens. He’d chop the chicken’s head off on a stump, toss the chicken to the ground, and it’d run around headless, blood spurting from its neck. To pluck them I had to dip the dead chicken into boiling water. Hot wet chicken feathers smell horrible, and I could never get all the tiny pointy pin feathers out of their skins. Fried chicken sure tastes good though.

I cleaned the chicken shit out of the chicken coops. It’s one of the nastiest jobs there is. Chicken shit gets dry and dusty, so as you shovel it, you breathe it, you wear it inside and outside your clothes. Another nasty job is moving hundred pound bales of hay from field to truck to hayloft. You’re hot, you’re sweaty, and all the sharp hay shards get inside your nose and clothes and itch and scrape and poke. Inside your nose and inside your clothes—sums up chicken shit, sums up hay baling.

Farm life was too much work for me. I don’t like to do things, especially at specified times. My one exception was milking the cow early in the morning. It was my favorite work. You’re sleepy, it’s still dark, you lay your forehead on the warm concave curve of the cow’s flank, and start going squish-squish! squish-squish! into the milk pail. To milk a cow, place both hands loose fisted around two teats of the udder, thumbs upward. Close your thumb and top finger together to block the milk from escaping back into the udder, then one by one bring the rest of your fingers together top to bottom into a closing fist to squeeeeze the milk out. First left, then right teat. The teat skin is normally dry and scaly, sometimes with small sores and scabs, so occasionally you need to rub ointment into it. If you irritate the cow too much, she’ll pick up her right back hoof and plop it down into the milk pail. The milk is quite warm out of the teat and froths as you squirt more and more into the pail. We had two cows because a cow dries up when pregnant, and then uses her milk to feed her calf. We bred the cows alternately so we always had milk to drink and a calf to kill. The breeder puts his whole arm up the cow’s anus to fertilize her.

We had free ranging cats, a miniature collie dog named Lassie, and a good natured white German Shepherd called Tippy. The worst smell in the country is when your dog comes back with skunk all over him. Soap and water won’t wash it off.

Because of the dirt country roads, we were mudded-in every spring, snowed-in every winter. Our first year we had to use the outhouse out back. We were poor, but we ate well. We had our own garden. We had beef, pork, rabbit, chicken, goose, infrequent duck and frequent venison. We ate chicken eggs, goose eggs and duck eggs. We churned our own butter and drank our own whole milk, which was one quarter cream on top. We sold a gallon of fresh milk for fifty cents, a pound of homemade butter for fifty cents, rabbits for fifty cents a pound. I used to kill rabbits. I’d hold them by their hind legs, put the club behind their head, push their head down a little bit, then qwack! them, slit their throats, pull their skins off like a coat, gut them, sell them, eat them. Rabbits squeal if you don’t hit them just right, a high squeeee. And just like the joke, rabbits fuck all the time. If you want to grow a lot of meat fast, buy rabbits, although sometimes the parents eat the babies.

The rabbits were supposed to be cameras. My first year in 4-H Club, I took photography. For the second year, I was required to have a dark room to develop my pictures and we couldn’t afford one, so I killed rabbits instead.

I walked a dirt road mile one way to a two-room white-wood school house. Two mad horses chased me each day as I walked by their field. Nearer school, vicious dogs tried to bite me. Though terrified of the path to school, I liked being there.

Grades One through Four were in one room, Five through Eight in the other. Thirty-six students total. One day in class I sat at my wooden desk sucking on the top of my pen. The pen cap came off and ink filled my mouth and I swallowed it. I went into the supply closet and read the back of the India Ink bottle. It said Poison. I went back and sat quietly at my desk, watched my classmates in silence while I waited to die.

We had two teachers, a husband and wife who lived in a cottage on the grounds. The husband gave me a single shot 22-caliber rifle when I was eleven. I saw a bird flying against the wind, shot straight up and killed it. I felt small and unclean when it fell from the sky. The only thing I killed after that was a bumblebee. Put the gun barrel right up against it, pulled the trigger, and blam, no more bumblebee.

My first brother Jay died from colic our first year on the farm. “Colic†sounds like a dog collar for Lassie, or a college for collies, or a country boy’s cowlick. They all fit too since we did live in the country in the midst of hay and wheat fields, had a miniature collie named Lassie, and set out salt licks for the cow.

Jay Curtis Smith was born late 1953. He cried nine months, then died. Seven year old me did not know the baby I’d looked in on that morning was dead; I only saw a very still, sleeping baby. Mom was acting odd, but moms frequently don’t make sense, so I said goodbye and walked my purgatorial mile of aggressive horses and angry dogs to the two room country school house up the lane.

After I got home that afternoon, Mom said, “Jay died last night.”

“Can I see him?” I wanted to see what death looked like.

“Sorry kid,” Mom said. “You can’t. He’s gone.†I felt cheated. I’d seen a dead baby, but had looked with the wrong eyes.

– Excerpt from Chapter One, Criminal by Smith & Lady.

view of top of cow barn and pond I used to play in from the top of my tree on our 40 acre farm in 1960.

In the foto at top of the blog, the barn is all the way to the left

and the tree I’m in taking this foto from is the tallest tree on the left half of the foto

foto by Smith, 1960