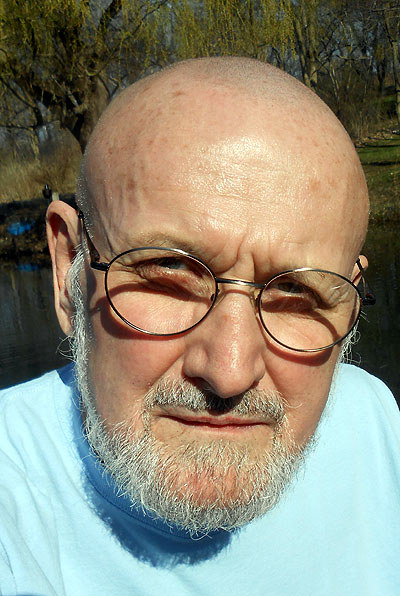

Sober 23

One more gone, go one more.

See what tomorrow has in store.

– Smith, 4.21.2014

23 years sober, starting 24.

Drank myself to death April 21 1991 and woke in intensive care. Three days later I rose from my dead and walked home to alcoholessness.

Alcohol was the hardest drug I ever beat . . . over the next nine years I quit NyQuil, cocaine, speed, pills, needles and everything else except for coffee, grass, and the occasional magic mushroom.

Still stride the fine fusion of self delusion, but wriggle in its grasp.

excerpt from my bio Stations of the Lost, a True Tale of Armed Robbery, Stolen Cars, Outsider Art, Mutant Poetry, Underground Publishing, Robbing the Cradle, and Leaving the Country by Smith & Lady, The City Poetry Press, 2012:

One night in April 1991 watching the movie Mortal Thoughts downtown with Mom, I started swallowing small amounts of liquid, which was odd because I wasn’t drinking anything. An alcohol induced ulcer at the base of my esophagus had hemorrhaged and I was swallowing my own blood. I came home scared and didn’t tell Mom.

While Mom was downstairs in her space, I lay in my loft for fourteen hours vomiting blood into a bedside bucket, passing out, coming back, all the time my little computer brain computing, saying, This is serious, you’re going to have to go to the hospital. But hospitals meant money and I was poor with no health insurance. I’d vomited blood the previous December for four hours and managed to stop it through will or luck so I thought maybe I could stop it this time, too.

For the first six hours I thought, Right now I can get up and drive to the hospital.

A couple hours later, more lost blood, more unconsciousness, I thought, Well now I can take a bus to the hospital because I’m too weak to drive anymore.

Later it became, Now I have to call a cab.

Each time I’d start to lose consciousness from blood loss, I’d think, Is this it? But each time I worried about Mom who still needed my help and company, so I came back. All through this, I collected the blood into the bucket and wondered, What art piece can I make with a bucket of my own blood? Buckets of human blood aren’t easy to come by, so this was a seriously unique art supply.

Finally I couldn’t do anything but weakly call over and over until I woke Mom. She called EMS. I was too heavy for them to carry down from the loft because I weighed ninety pounds more then from all the wine and food. I rolled out of my waterbed, crawled on my belly across the floor and slid like a seal head first down the loft stairs where they put me onto a sling and carried me to the ambulance, where I immediately disappeared into unconsciousness. When I returned to this reality after an indeterminate period of time I looked at the nurse and croaked, “Wow, nice to be back,” and threw up a huge amount of gelatinous blood. It looked like pre-chewed Jell-O quivering in her tray.

Oh, I was gone. I mean, I left my body. Before—in the fourteen hours of vomiting blood—I would occasionally lose consciousness and there’d be a nether region where I was aware I might not come back and then I’d worry about Mom and return. But down in the ambulance I zoomed right past that point. I was gone. When I regained sight, it was literally, Wow, I’m back, and it felt good. I was glad.

I officially quit drinking in intensive care the third time they shoved the tube up my nose and down my throat. The first two times I gagged the tube back out with my throat muscles. I decided right then that if I lived I would never have a tube shoved up my nose again due to alcohol, and I haven’t drank since.

The docs dripped six units of blood into me. After the fifth unit one doctor turned to the other two and said, “Where’s it going?” A friend inquired later if I knew what type blood I’d received. I said, “No but the next time I went downtown I bought a five hour boxed set of James Brown music.”

Back home, Mom dumped my blood bucket because the rot smelled bad. Everyone’s an art critic.

After I stopped drinking Mom admitted to me, “It was so bad living with your drinking I was thinking of moving out.”

“Where would you have gone?” I asked.

“I had no place to go,” she said, “but I couldn’t have stayed with you the way you were.”

I got a call from Dick Head while still in the hospital. “I can’t drink anymore or I’ll die,” I told him.

“Then why don’t you die!” he screamed. “I’d rather die than not drink.”